In the days and weeks since the release of the six-part series on PBS, it has come to our attention that the American Revolution documentary may not be factually accurate.

To be transparent, we are posting articles exposing inaccuracies presented in The American Revolution documentary series. Should PBS and/or Ken Burns respond to these criticisms, we will post those as well.

Truth matters. As we celebrate the 250th Anniversary of the founding of our nation, as American citizens, it is incumbent upon us to perform our civic duty to know our history and to live and defend the truth of it.

November 25, 2025

Ken Burns Is Off To A Hard-Left Start With His American Revolution Series

By <www.americanthinker.com/author/s_david_sultzer/> S. David Sultzer

Ken Burns and PBS want to teach us the history of the American Revolution. That’s objectively laudable, but from the opening seconds of his new six-part, 12-hour-long series on the Revolution, Burns is off to a truly ludicrous start. Why do I say that? Because instead of beginning with the events that led to the break with Britain in 1775, Burns (after an anodyne quote from Thomas Paine) opens with an Indian diatribe about land.

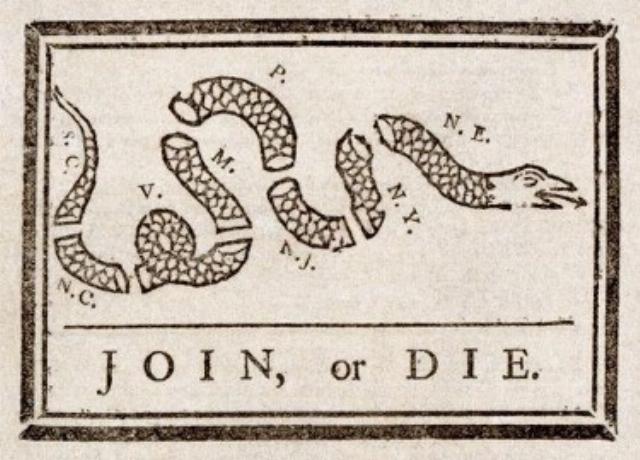

Public domain.

That is not surprising. Lest there be any question as to what Burns intends for us to learn about the American Revolution, Burns stated in <www.npr.org/2025/10/20/nx-s1-5580245/ken-burns-american-revolution-series-includes-voices-the-founders-overlooked> an NPR interview on Oct. 20, 2025, that he believes the driving force of the American Revolution was not to secure for all Americans the ancient rights of Englishmen, but to steal land from the Indians. Really:

The central [motivating force], we’re not taught this in school. It’s taxes and representation, which is super important, but it’s Indian land.

This is obscene historical revisionism. While it’s true that many people wanted to negotiate with Indian tribes to purchase land in the west, that is where the evidence ends. Yet Burns flogs this canard repeatedly throughout the first half-hour of Episode 1.

To go beyond that and claim that a desire to steal Indian land motivated the colonists generally—or the Founders particularly—to rebel against Britain lacks a single iota of fact in a massive historic record. Burns’s claim is based on nothing more than—to <www.bookwormroom.com/2021/10/11/analyzing-how-leftism-destroys-intellectual-honesty/> quote Professor Sean Wilentz’s masterful condemnation of the 1619 Project for similar unsubstantiated calumnies—“imputation and inventive mindreading.”

Moreover, Burns ignores the entire political history of Britain—and that history shows that, for Englishmen, the single most abused power of government was taxation. More English blood had been spilled over that one issue than any other in the history of England.

Every major civil war and coup in England—and all three of the resulting documents that articulate British rights—started with a King imposing taxes unilaterally, without approval from the people through Parliament or its predecessor, the Great Council, to which the barons and church leaders belonged. That was true of <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John,_King_of_England> King John in 1215, when he was forced to sign the <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magna_Carta> Magna Carta when <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Barons%27_War> his barons rebelled. It was true of <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_I_of_England> Charles I, who ignored Parliament’s <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petition_of_Right> Petition of Right, a decision that led to <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Civil_War> a civil war that ended with his beheading. And it was true of <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_II_of_England> James II, whose despotic reign led to his being overthrown <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glorious_Revolution> in a 1688 coup that gave rise to England’s <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_of_Rights_1689> Bill of Rights of 1689.

Just 75 years later, in 1764, the Sugar Act—which imposed a tax on the colonists without their being represented in Parliament—led to James Otis, Jr., the famous Massachusetts lawyer, to articulate <oll.libertyfund.org/pages/1763-otis-rights-of-british-colonies-asserted-pamphlet> the bedrock principle of the colonists:

When All persons born in the British American Colonies are, by the laws of God and nature and by the common law of England, entitled to all the natural, essential, inherent, and inseparable rights, liberties, and privileges of subjects born in Great Britain or within the realm.

This statement had nothing to do with gaining Indian land, whether by purchase or conquest. It had everything to do with the rights of Englishmen won in the bloody civil wars fought since 1215 A.D. Instead, he referred entirely to the rights that Englishmen had acquired over more than 500 years of battle against their government. And the seminal civil right, first articulated in the Magna Carta of 1215, was that the government could not impose taxes without approval from the people’s representatives.

In 1766, when <founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-13-02-0035> Ben Franklin testified to Parliament about why the colonists were in open revolt against Britain over the <grokipedia.com/page/Stamp_Act_1765> Stamp Act, he did not mention Indian Lands. He traced the unrest solely to Parliamentary acts taxing the colonists when the colonists were not represented in that body. Outrageously, Burns actually repeats some of Franklin’s testimony, but then cuts it off before Franklin attributes the unrest to taxation without representation. Thus, this is what Burns uses in the show:

Q. What was the temper of America towards Great-Britain before the year 1763?

Franklin: The best in the world. They submitted willingly to the government of the Crown, and paid, in all their courts, obedience to acts of parliament. Numerous as the people are in the several old provinces, they cost you nothing in forts, citadels, garrisons or armies, to keep them in subjection. They were governed by this country at the expence only of a little pen, ink and paper. They were led by a thread. They had not only a respect, but an affection, for Great-Britain, for its laws, its customs and manners, and even a fondness for its fashions, that greatly increased the commerce…

Had Burns been an honest broker, he would have included what Franklin said when asked about the changes in colonial attitudes to the mother country:

Q. And what is their temper now?

Franklin: Oh, very much altered.

Q. Did you ever hear the authority of parliament to make laws for America questioned till lately?

Franklin: The authority of parliament was allowed to be valid in all laws, except such as should lay internal taxes. It was never disputed in laying duties to regulate commerce…

To say that the Revolution started over greed for Indian land is stunning revisionism. But Burns gets worse.

After asserting that Americans fought their revolution to steal Indian land, Burns moves on to the <grokipedia.com/page/French_and_Indian_War> French and Indian War. It’s a reasonable chronological organization, as the American Revolution would not have happened—and happened the way it did—but for that war. That’s because the war led Britain into debt, which it sought to ease by taxing the colonies.

Further, the war made the reputation of George Washington, the man who <www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/jumonville-glen-skirmish> ignited the French and Indian War and emerged from it as the <www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/battle-of-the-monongahela> Hero of Monongahela. All of these things were critical to igniting the American Revolution and to the Continental Congress’s later choice of George Washington, the indispensable man, to command the Continental Army.

Burns could have started with any of those salient points—and he eventually gets around to most of them later, after having already driven home his revisionist points. Instead, he starts the show with a footnote to the French and Indian War. Burns raises <founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-04-02-0037?utm_source=chatgpt.com> Ben Franklin’s short commentary on the <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iroquois#Confederacy> Iroquois Confederacy and credits the Confederacy with being both the model for Ben Franklin’s <grokipedia.com/page/Albany_Plan> Albany Plan and, “20 years later,” for the design of the government that the Founders chose for the new United States.

There is not a single primary source document that supports any of that. The notion that Franklin linked the Albany Plan to the Iroquois is pure modern revisionism. To say that British colonists only discovered confederations, or democracy, or the separation of powers from the Iroquois Confederacy is laughable.

By the time 1754 rolled around, all British citizens with an education were steeped in history. They were intimately familiar with the republic of <grokipedia.com/page/Roman_Republic> ancient Rome in 509 BC, the virtues and weaknesses of democracy from <grokipedia.com/page/Athenian_democracy> ancient Athens in 508 BC, and the workings of confederations, which had <grokipedia.com/page/Twelve_Tribes_of_Israel> existed since the Tribes of Israel joined together after the Exodus in 1,446 BC. By 1754, the most famous confederacy in Europe was the centuries-old <grokipedia.com/page/Holy_Roman_Empire> Holy Roman Empire, of which the British King was an “elector” for Hanover. And the British, with the <grokipedia.com/page/Magna_Carta> Magna Carta of 1215 and the creation of elected <grokipedia.com/page/Parliament_of_England> Parliament in the 14th century, had created far more democratic institutions with stricter separation of powers than the Iroquois Confederacy ever dreamed of having.

Franklin, obviously long familiar with the notion of a confederacy, was saying only that if the Iroquois could do it, anybody could.

Moreover, nothing in the <www.loc.gov/item/05000059/> Congressional Journals of the 1st and 2nd Continental Congress gives any hint that the Iroquois Confederacy was used as a model either for Congress or the <www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/articles-of-confederation> Articles of Confederation that John Dickinson drafted. Nor is there mention of the Iroquois Confederacy in <avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/debcont.asp> Madison’s Notes on the Debates in the Federal Convention. In short, all claims that the US government was based on or borrows from the Iroquois Confederacy are groundless.

Others have raised similar points.

The Iroquois influence thesis, suggested here by Ken Burns in his new documentary on the American Revolution, has been thoroughly debunked by academics and historians 🧵 <www.americanthinker.com/articles/2025/11/%E2%80%9Chttps:/t.co/sRSVP9mL7W%E2%80%9D> pic.twitter.com/sRSVP9mL7W

— Jonathan Barth (@Professor_Barth) <www.americanthinker.com/articles/2025/11/%E2%80%9Chttps:/twitter.com/Professor_Barth/status/1991604372585996438?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%E2%80%9D> November 20, 2025

I teach US History in a public school.

The “Iroquois influence” claim started in the 1960s–70s as part of the Congressional “Indian Self-Determination” movement. Historians across ideological lines (including Native scholars) have pointed out: – Zero primary sources from the…

— Ninety Degrees (@quasiantipodean) <www.americanthinker.com/articles/2025/11/%E2%80%9Chttps:/twitter.com/quasiantipodean/status/1991599721572626785?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%E2%80%9D> November 20, 2025

In 1997, PBS broadcast a six-part series, Liberty! The American Revolution, that was a fair and honest retelling of the history of the American Revolution, warts and all. Three decades on, if the first episode is anything to go by, this latest offering from PBS and Ken Burns appears to be neither fair nor honest. Indeed, PBS and Burns seem to be giving us a narrative of American history <www.historynewsnetwork.org/article/howard-zinns-biased-history> worthy of Howard Zinn.